Alejandro Alvarado &

Concha Barquero &

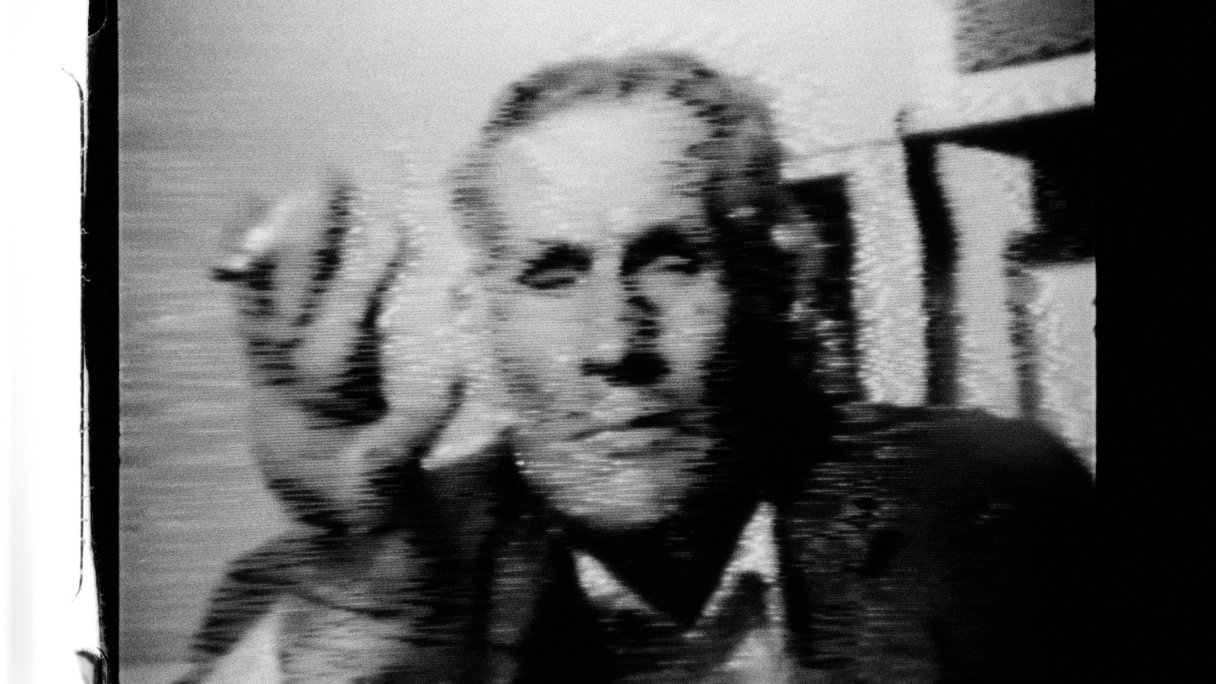

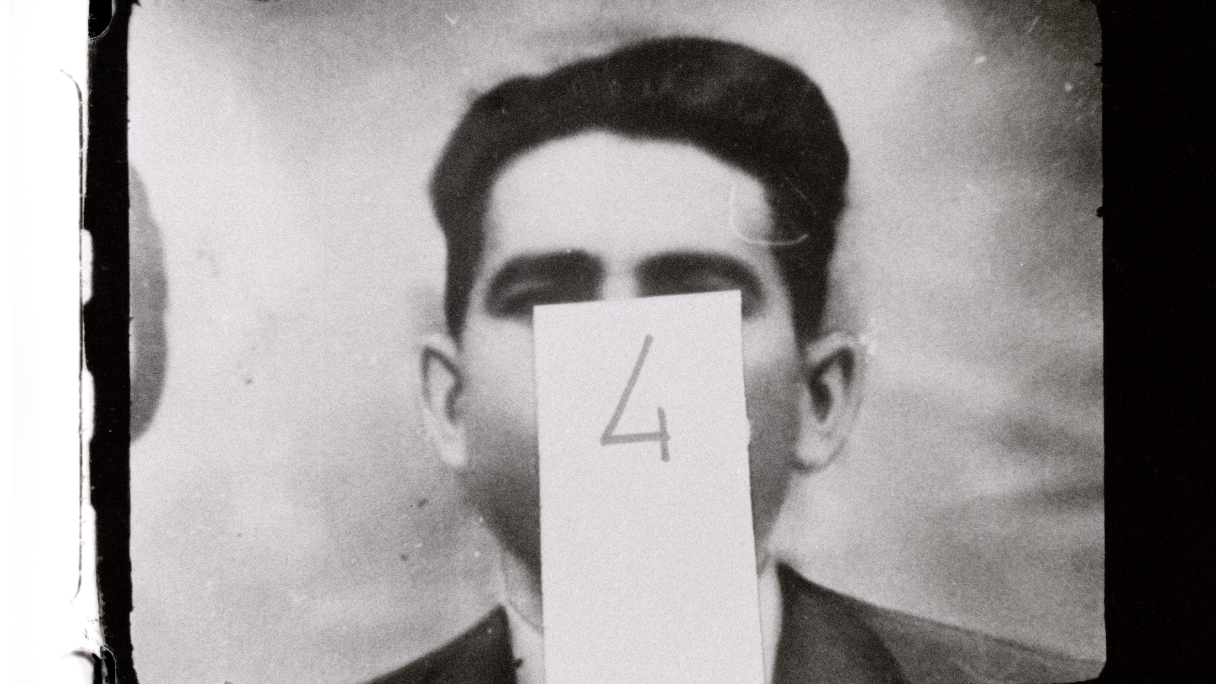

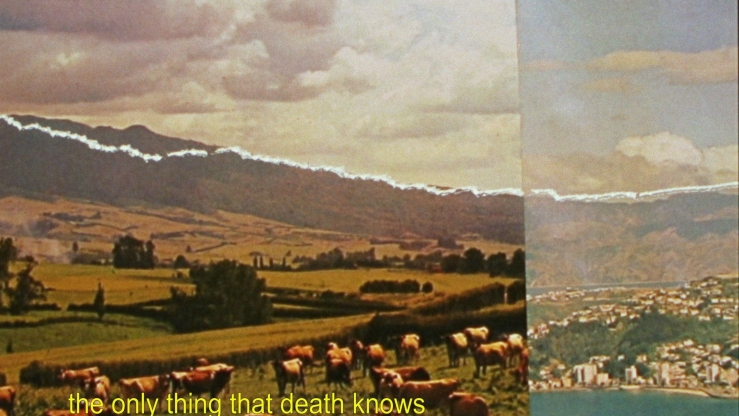

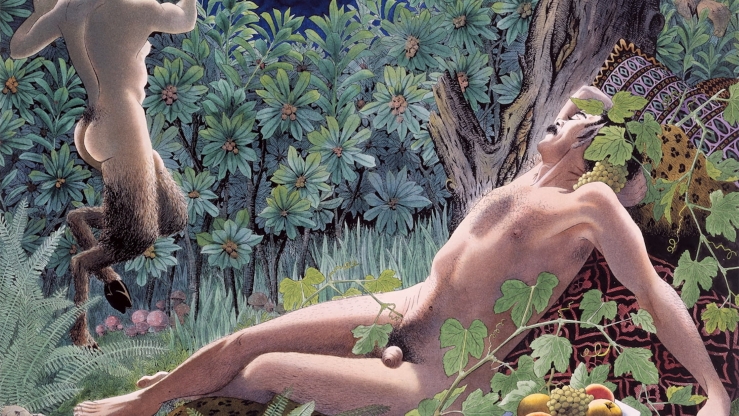

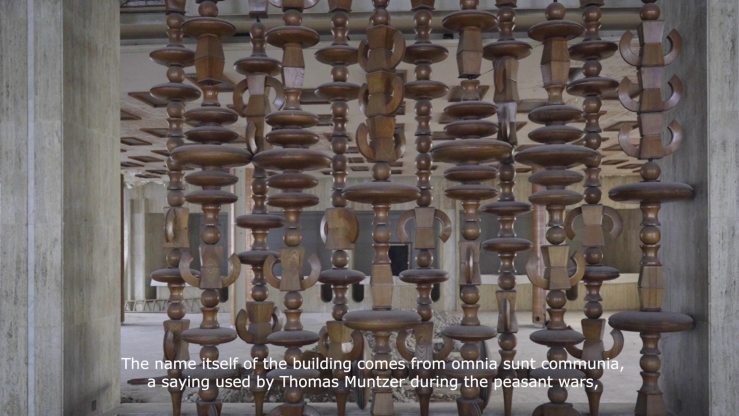

DESCARTES by Concha Barquero and Alejandro Alvarado is a filmic treatment of Fernando Ruiz Vergara’s documentary film Rocío (1980), which until this day is subject to censorship in Spain. Rocío, which refers to the famous place of pilgrimage El Rocío, was created together with scriptwriter and producer Ana Vila as well as with the support of Portuguese film cooperatives, which provided technical resources. The film caused a great deal of controversy and, despite the fact that the prior censorship measures concerning film productions under Francoism had already been abolished in 1978, it was confiscated by the court, while Ruiz Vergara was both fined and sentenced to prison. What was deemed problematic was not the documentation of the Pentecost pilgrimage — in fact, the obvious intention of shooting a mere documentary about the historical, sociological, cultural, religious, and anthropological dimension of the pilgrimage was recognized as such — but rather scenes depicting witness statements, particularly Pedro Gómez Clavijo’s, which dealt with the suppression and murders committed by Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in the municipality of Almonte during the Spanish Civil War in July 1936. His testimony made it possible to unambiguously identify a certain Mr. Reales as a fascist criminal.

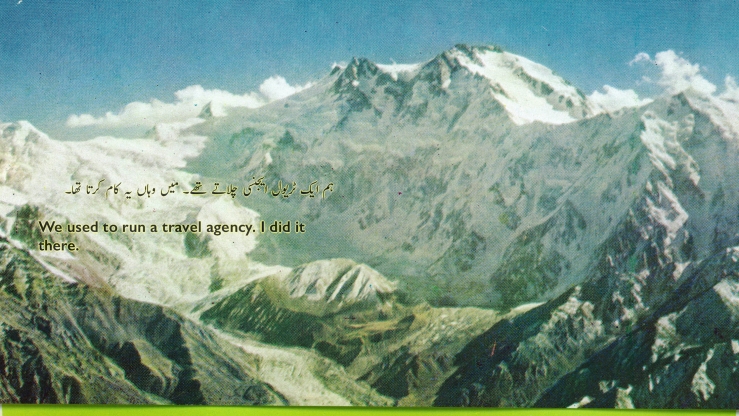

In 2010, Barquero and Alvarado met with Ruiz Vergara shortly before his death in order to conduct an interview about the subject of censorship in documentary films. In 2016, they conducted archival research on the film in the Filmoteca Española (Spanish Film Library). Here, they found 260 reels of 16 mm film including outtakes, meaning material that was shot but not included in the final cut. DESCARTES is based on these outtakes, whose original soundtrack was not preserved. The silent images are supplemented with voiceovers and explanatory texts, which are superimposed at the beginning, the middle, and the end of the film. Off-screen, excerpts from the verdicts spoken by the municipal court of Seville in 1982 and the Supreme Court of Spain in 1984 are read by the poet María Eloy-García. Additionally, the historian Francesco Espinosa Maestre reads from sections of two of his publications. Relevant in this context is that he compiled a list of citizens who either disappeared or were murdered between the years 1936 and 1939, which was put together on the basis of the film. Seven names appear in the outtakes.

Like Ruiz Vergara and Vila, who dedicated themselves to political activism in the form of filmmaking, Barquero and Alvarado once again raise questions concerning freedom of speech, historical memory, and compensation. That Rocío is subject to censorship until this day, and that the events in Almonte have not been satisfactorily dealt with, make the film even more significant. (Lisa Bosbach)

Supported by Vicerrectorado de Cultura de la Universidad de Málaga (UMA)

Images: Concha Barquero & Alejandro Alvarado, Descartes, 2021 © Concha Barquero & Alejandro Alvarado, Fernando Ruiz Vergara

About the artists

About the Work

Insights at Videonale X